The Progressive and Regressive Messaging of Devdas (2002)

There is so much to like about Devdas (2002). But also much with which to have concern. In some scenes, the film pushes against ideas of worth as dictated by men and society. But in others, a link between violence and love is drawn and in some ways, glorified.

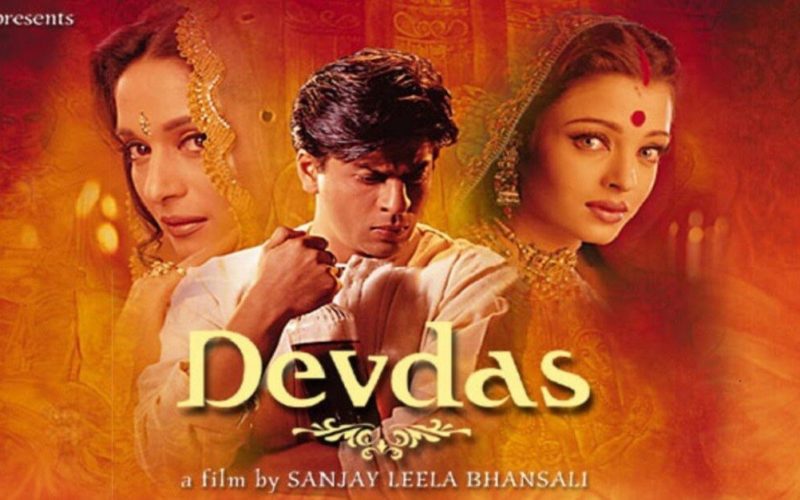

Devdas is the tragic love story of Devdas (Shah Rukh Khan) and Paro (Aishwarya Rai Bachchan), and is set around 1900. Devdas and Paro are childhood friends, and in their minds, made for one another. With their special relationship in mind, Paro’s mother, Sumitra, seeks approval for their marriage from Devdas’ mother, Kaushalya. In this attempt, she spurned, as Kaushalya believes that Sumitra’s background as an actor and a dancer makes her and her family inferior.

In the turmoil that follows, Paro accepts a marriage proposal from another man. In despair, Devdas turns to drinking, and is held from the abyss of alcohol poisoning only by the care of Chandramukhi (Madhuri Dixit), a dancer from the city’s red-light district. The film is ultimately the story of the pushes and pulls of love and rejection between Devdas, Paro, and Chandramukhi.

Here is a trailer for the film.

As indicated above, there is much to appreciate about Devdas, but also much for concern.

In appreciation

Devdas is a stunning film. Under the direction of Sanjay Leela Bhansali, and in a trend apparent in his films since, every frame is striking, every color radiant. See the below song, Silsila Ye Chaahat Ka, for example.

Moreover, in Chandramukhi and Sumitra, Devdas presents a narrative that deserves to be told. Namely, that profession is not a measure of someone’s humanity. And further, that while the perceived worth of one person is measured in juxtaposition to that of another, the scales are inherently skewed by classism, patriarchy, and hypocrisy.

In one scene, Paro’s mother Sumtria dances for the family of Kaushalya, Devdas’s mother. She had come to their home with under the impression that a marriage was to be arranged between her daughter and X’s son. When the performance concludes, Kaushalya, instead of thanking Sumitra for her effort, accuses her of trying to manipulate a marriage between the families to acquire status and wealth.

In disgust of the idea of her family linking with that of Sumitra, she says, “Why draw water from poisoned wells? You may not betray the traits, but your genes remain the same, that of the dancing girls…Don’t you try to palm off your bad coin”. She is basically saying, that as Paro’s family comes from a line of dancers, their status will never equal that of her family’s.

“Enough!” Sumitra yells back, “Replying to you is beneath my dignity”. She then explains that a status based on profession is no substitute for worth, and outlines the years of support and love she had shown to Devdas.

The theme of profession and status, as well as of gender equality, is additionally addressed in scene in which Paro invites Chandramukhi to her home. There, in front of Paro’s new in-laws, they dance together as friends. As their dance concludes, a local aristocrat, and frequent brothel client, disparages Chandramukhi for her profession, much as Kaushalya had insulted Sumitra for hers. A relative of his adds, “Company of the aristocracy doesn’t confer status to the courtesan”. He also seeks to embarrass Paro for her friendship with Chandramukhi.

Chandramukhi retorts, “It is the aristocrat who brings cheer to the brothels”, indicating that aristocrats may disparage brothels, but some of those same people attend them. In defense of Paro she says, “Why should the lady be embarrassed if she spoke a few kind words to me, because she considers me human?… He who frequents the alleyways of disrepute ought to be ashamed”. This scene is similar to that in Dirty Picture, which I cover in an earlier post, in which Silk (played by Vidya Balan) notes a collective responsibility for provocative dancing in films, and pushes back at being scapegoated for it.

The above-mentioned scenes underscore some of the important and progressive messages present in Devdas. Namely, that family background and profession is not the ultimate arbiter of someone’s inherent worth, and that society’s conceptions of worth are not immune to the sways of sexism, classism, and so many other isms and prejudices for that matter, that judgments drawn from them are often questionable, at best.

For concern

Unfortunately, Devdas is a conflicted picture. The film certainly contains some progressive messages, but these messages are substantially undermined by other themes within the film. Specifically, the relationship between Paro and Devdas is deeply concerning. It’s a love story interweaved with violence.

I noticed this theme in the song Bairi Piya, where Devdas attempts to adorn Paro’s arm with a bangle. She resists and he persists, and while the back and forth is presented as playful, forcefulness is clearly a theme. See below.

But there is one scene in Devdas that rises above the others in glorifying links between violence, possession, and love. In the scene, as Paro is preparing for her wedding to another man, Devdas expresses his lack of approval. Paro, who had waited for him for many years, only to have him initially fail to stick up for their love, explains that with her marriage, her public status would exceed that of his, and that that would combine with her already existing worth. She would be his equal, she says.

In frustration, Devdas says, “not even the moon is as vain”. When Paro responds, “But the moon is scarred”, Devdas hits her across the head with a chain of pearls, and says, “I have scarred you like the moon with the mark of my love”. He then pushes blood from her forehead to her hair, a reference to the vermillion mark that is placed on a woman’s head at marriage. She let’s Devdas brush the blood into her hair and wears the scar with pride.

To make it worse, the film lacks any introspection about this event from the characters, both when it happens and in its wake. Instead, the film goes on to focus on the tragedy of Paro and Devdas’ torn relationship, never addressing the unhealthy nature of it to begin with. Women are not property to be marked with a seal of ownership. Nor is violence against women ever justified. In not addressing these issues, the film implicitly, even if without intent, does just that.

As Devdas is based on a book (1917), I wonder if more reflection is afforded to this dynamic in that medium, or in its other film adaptations. Unfortunately, in this film, violence is used more to illustrate the intensity of Paro and Devdas’ relationship than the danger within it.

Title image source

I love this Dave! Keep it up!