The Complex and Conflicted Relationship Between Film and Politics in South Asia

Films connect people. For the few hours that an audience sits together in a theater, they share experiences and emotions; they see the world through the same lens, projected on the same screen. And with the global proliferation of online streaming platforms, the lenses are increasingly diverse, the screens increasingly different, and the audiences counted in the millions.

In an earlier post, I shared some of my thoughts on the changing nature of international film production and its possible influences on global culture. I’m proud of that post, but it demands a revisit.

It demands a deeper look. Films are certainly capable of transcending international borders and connecting diverse viewers, of creating a more global culture. But then again, they’re also capable of not doing those things.

This post focuses on the latter, on how films can be effected by, and effectual of, the division of audiences around them. Specifically it asks: what does it mean when film can increasingly transcend national borders in a world where many borders remain markers of interstate tension and conflict?

Unfortunately, this dynamic can be found in South Asia, where geographic and historic factors unite India and Pakistan in a common linguistic heritage, where films and television shows are made and enjoyed on both sides of the border, and where conflict divides two countries with so much in common.

Film and politics in South Asia – a historic relationship

South Asia is home to a variety of film industries, each producing in a different language. Fortunately, subtitles, dubbing, and the regional commonality of knowing more than one language allow for these films to be enjoyed among diverse audiences.

This, in short, is how Indian films have found enormous popularity in Pakistan, and how Pakistani TV dramas have garnered fans in India.

But despite the ease with which many Indians and Pakistanis can understand one another’s cinema, exchange of this commodity is a relatively recent affair.

In fact, following the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965, Indian films were fully banned in Pakistan. The war, like many armed conflicts between India and Pakistan, centered on the mountainous region of Kashmir. Since the partition of India and Pakistan in 1947, this area, wedged between India, China, and Pakistan, has been the focus of continuous territorial dispute.

In 1998, the Pakistani ban of Indian films was lifted and Indian films flooded the country. But the link between politics and film was never fully severed. It lives on today, with recent events in South Asia offering tragic evidence.

The freeze and thaw of cross-border film collaboration

In September 2016, a deadly attack in Kashmir led to Indian airstrikes in Pakistan. When the brief moment of violence passed, relations between India and Pakistan were deeply soured.

It wasn’t long before this souring spread again to the world of film. What started on the battlefield would continue on the set and in the theater.

In India, film associations announced bans on the future employment of Pakistani actors. In Pakistan, theaters closed their doors to Indian films.

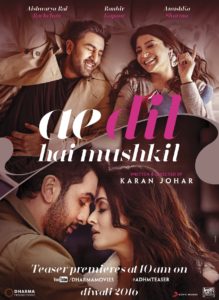

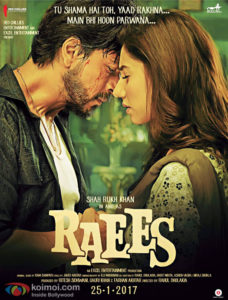

Coincidentally, this cross-border chill occurred right as two of Pakistan’s biggest stars, Fawad Khan and Mahira Khan (no relation), were soon to star on the big screens of India – in Indian-produced films; Fawad Khan in Ae Dil Hai Mukshil (2016) and Mahira Khan in Raees (2017).

Fawad Khan had already starred in Indian-produced Kapoor and Sons (2016), and both he and Mahira Khan had garnered sizable Indian fan bases for their work in the Pakistan TV series, Humsafar. But this time, the context was different, and Ae Dil Mukshil’s upcoming release became a quick target for public discontent.

With pressure mounting against Ae Dil Hai Mukshil, the film’s director, Karan Johar, released an online video in which he promised to no longer employ Pakistani actors in his films, and asked that fans support the film and the many Indians who had worked on it.

Raees star, Shah Rukh Khan, made a similar pledge and added that Mahira Khan would not be joining him during Raees’ promotional events in India.

Ae Dil Hai Mukshil and Raees released in India, but not in Pakistan.

But the freeze did not last long, and on January 31, Pakistan’s Ministry of Information, Broadcasting and National Heritage released a statement indicating that Indian movies were once again welcome in the country.

Rakesh Roshan, the producer of Kaabil, an Indian film released around this time, encouraged Indian film distributors to share their films once again with Pakistan as the ban had been lifted – “All I want to say is that if Pakistan has opened their arms, we should also move forward.”

Looking forward

Today, roughly five months after violence pulled India and Pakistan closer to war, Indian films are once again screening in Pakistan, and Pakistani actors are once again on the screens of India. But that doesn’t mean everything is business as usual. People have died and relationships have soured.

Further, the events of the past months have raised important questions for the film industries of India and Pakistan, as well as for the audience. And while asked within the context of South Asia, these questions reflect themes that apply across the world.

Most immediately, for how long will Pakistani actors continue to face a ban in India? If the ban is lifted, how long will it take for relationships to heal and for Pakistani actors to return to India? Will they?

In the long term, will film and actor bans remain a tool of politics in South Asia? Should they? What does this mean for artistic freedom? Who do they help; who do they hurt? The Guardian, for example, reports that roughly 70 percent of Pakistani cinema income is derived from the screening of Indian films.

Lastly, how long will these questions even remain relevant? With the increase of Internet access and of online streaming, the relationship between film and international borders is changing.

In the photo below, you’ll see Pakistani-actor Mahira Khan, barred from work in India, promoting Raees alongside her Indian co-stars. She’s in Pakistan, but through an internet-supported video call, she was able to connect with her fans in India.

I conclude with this image, because it seems an illustrative example of the many complications (and possibilities) present in the modern-day intersection of film, politics, and our increasingly inter(net)-connected world.