How Geography Explains the Linguistic Complexity of South Asian Cinema

South Asia is home to many film industries, each catering to a different linguistic community. In North India, films are produced in Hindi, Marathi, and Bengali, to name a few, while in the South, moviegoers watch films in languages such as Telugu, Tamil, or Malayalam. Moreover, films are enjoyed across borders, with Hindi-language productions finding huge popularity in Pakistan, and Pakistani television dramas captivating audiences across India.

So what explains all of this? Why does India have so many film industries and for so many languages, and why are Hindi films so popular within Pakistan, one of India’s neighbors, and not as popular in China, one of its others? The answers to these questions have roots in geography, and in this post, I hope to walk you through the role of geography in shaping the evolution of South Asian languages, and in turn, the linguistic complexities of the region’s modern movies.

Geography and Migration

The history of India, E. J. Rapson wrote in 1914, “is in a large measure the story of the struggle between newcomers and the earlier inhabitants,” a struggle greatly shaped by “the geographical barriers which nature itself has set up” (1). In this regard, the region’s northern and mid-section mountain ranges are perhaps the most important.

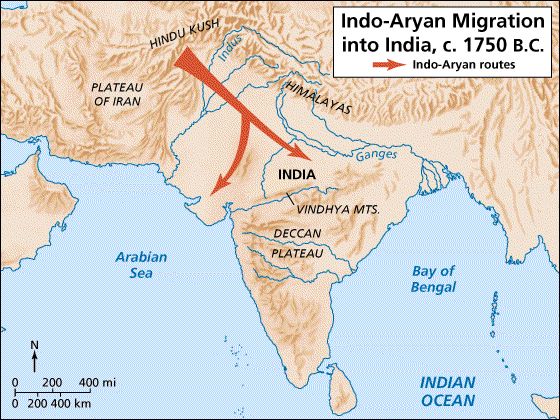

In the North, the Indian subcontinent is geographically cut off from the rest of Asia by a mountainous wall that stretches from Afghanistan to Burma. This wall largely isolated India for centuries from the cultural influences of Chinese civilization to its north, and other influences from its west.

But this isolation was not without exception, and these exceptions, too, were influenced by geography. While daunting, the mountain wall has a few cracks and openings, one of which is located where the mountain valleys of Afghanistan descent into the fields of Pakistan.

Few geographic quirks are more important to the development of world history in general, and to South Asian linguistic evolution specifically, than this small opening, because it was through here that Indo-Aryan peoples descended into the Indian Subcontinent (which includes the land that now forms India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh). This happened roughly 3000 years ago.

Geography and Language

With their migration, Indo-Aryans brought both the linguistic foundations of many North Indian (and Pakistani and Bangladeshi) languages, and important religious building blocks for what would become Hinduism, and in turn, Buddhism. Among the modern languages that branched from this common root are Hindi, Marathi, Gujarati, Punjabi, and Bengali. Further, during subsequent migrations (some of which were invasions) Persian vocabulary and script entered the region, permeated local conversation, and formed the language Urdu.

Importantly, the spread of Indo-Aryan languages did not extend across all of South Asia; the spread was halted within its interior. Geography, and specifically, the Vindhya Mountains, is a major cause for this, because the Vindhya Mountains, “with their almost impenetrable forests”, draw a “great dividing line between Northern and Southern India.” In short, if it weren’t for mountains, the Dravidian languages of the south, such as Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam and Kannada, may not have existed today.

Geography and Movies

So what can we take away from this (very brief!) history that can help us understand South Asian cinema today? Lots! But, I’ll focus on three overarching themes.

- Due to its complex history of migration, invasion, and integration, South Asia is one of the most linguistically diverse regions in the world.

For the world of movies, that has meant that unlike many countries, India has multiple prolific film industries, each catering to a different language group. Among the region’s major film industries are those that produce in Hindi, Punjabi, Malayalam, Tamil, and Telugu. Unfortunately, this diversity is often concealed behind the mistaken use of ‘Bollywood’ as a catchall term for Indian cinema. More on this misunderstanding can be found here.

- Languages of shared Indo-Aryan heritage are most commonly spoken in the South Asia’s north, while languages of shared Dravidian heritage are most commonly spoken in the region’s south.

In Indian cinema, this trend has led to the commonality of remaking existing movies. Specifically, it is common for films that have been released in one or multiple South Indian languages to be completely remade in Hindi, or for the same to happen in reverse. Importantly, many people who speak one Indo-Aryan language, or one Dravidian language, additionally speak, or at least understand, some of the others languages within the same language family – thus movies (at least as far as I can tell) are rarely remade in a language from the same language family. Instead, such movies are dubbed (where the voices are rerecorded, but the film remains the same).

But with India’s different languages represented by distinctively different film industries, completely remaking films allows moviemakers to present their audiences with actors within whom they are particularly familiar, and likely eager to see. This happens all the time between North and South Indian films.

- The region’s modern-day political borders are drawn across areas of shared linguistic heritage.

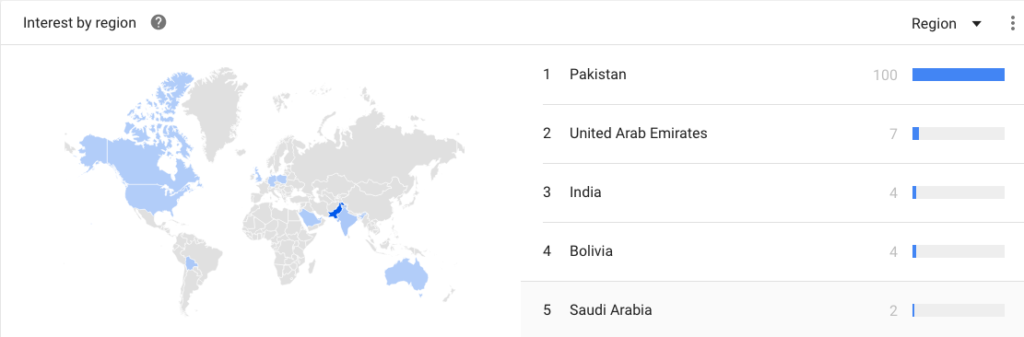

In population numbers, this dynamic is most starkly seen on the India-Pakistan border, which is hugged on either side by speakers of Urdu and Hindi (languages so similar that some use the term Hindustani to indicate their colloquial amalgamation). For cinema, this has meant that Indian Hindi-language movies are extremely popular in Pakistan. And more recently, a similar dynamic has happened in reverse, as Pakistani television dramas have gained huge followings in India.

A quick search on Google Trends illustrates this point. For example, when one searches “Shah Rukh Khan”, an extremely famous Indian Hindi-language actor, in Google Trends (which shows the popularity of search terms over given periods of time), this is what one sees.

Search popularity for Shah Rukh Khan over five year period (worldwide)

There’s so much going on here. There’s the popularity of Shah Rukh Khan in East Africa, South Africa, Europe, and North America, which likely represents, at least in part, the large communities of South Asian descent in these countries. There’s also the popularity of Indian cinema in Bolivia that I explored earlier (and am still looking into to). But most importantly to my above point, you can see that Pakistan leads the world in search density for Shah Rukh Khan.

Similarly, when I search Zindagi Gulzar Hai, a popular Pakistani-produced (Urdu) television show, the following is shown; namely, the show’s popularity in both Pakistan and India, where it was also released (as well as in Bolivia, among other countries).

Search popularity for Zindagi Gulzar Hai over five year period (worldwide)

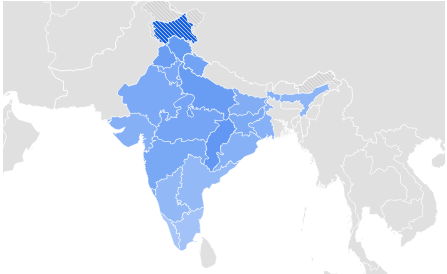

Additionally, if one views the term popularity in India specifically, you’ll see that it is most popular in the country’s north, with the areas in dark blue (and thus noting particular popularity) following very closely the linguistic distribution of Indo-Aryan languages, as shown in the map above.

Search popularity for Zindagi Gulzar Hai over five year period (India)

Importantly, the linguistic similarities between Hindi and Urdu have led to high profile actors from Pakistan featuring in Indian-produced Hindi films. Recent examples include Pakistani actors Fawad Khan and Mahira Khan starring in the Indian films Kapoor and Sons (2016) and Raees (2017), respectively.

But this trend has not been without resistance, as the realities of political geography, of tensions between India and Pakistan, have maintained barriers to such cooperation. In fact, it was Fawad Khan himself who was placed in the spotlight when Indian director Karan Johar indicated that he would no longer employ Pakistani actors after a series of military clashes in the disputed region of Kashmir.

Geography and the Future of Film

In an earlier post, I discussed the importance of the Internet in connecting the world’s people, suggesting changes in the way movies will be made, the languages in which they will be released, and the people they may reach. With the peoples of the world likely growing communicatively closer and closer in the decades to come, it will be interesting to see if the content and language of film will continue to expand past the age-old constraints of geography.

(1) Rapson, E.J. Ancient India: From the earliest times to the first century, A.D. University Press, Cambridge (1914)